Extramarital affairs are fairly common. Estimates are that by the age of 60 somewhere between 50-60% of men and 40-50% of women will have had at least one incident of extramarital sex.

Affairs are generally very intense and passionate and sometimes loving but tend to end painfully in an average of 2 years. However both men and women who have had affairs consider it a good experience. Some affairs evolve into intimate friendships, and those that do can last a lifetime.

A major motive for having an affair is dissatisfaction with one’s marriage. In fact many who have affairs claim that it helps their marriage, but the evidence is that affairs do not stabilize marriages. The desire for a new mate may be compelling and seemingly irresistible but having an affair is very risky because a fairly high percentage of divorces are the direct result of infidelity.

Slightly less than 15% of couples are currently in marriages where they agree that it is acceptable to pursue sex outside their marriage however most partners deceive their spouse rather than negotiate an open marriage. Furthermore open marriage is not a successful means of preventing divorce. More than half of all open marriages end in divorce.

Another option is swinging. In swinging both partners in a committed relationship agree, as a couple, for both partners to engage in sexual activities with other couples as a recreational or social activity. It provides sexual variety, adventure, the opportunity to live out fantasies as a couple without secrecy and deceit, and the possibility of reconnecting physically and emotionally. About 5% of married couples have been engaged in swinging at some time. Active swingers tend to be happier with their sex life, marriages and life in general than non-swingers, and women were just as happy with the arrangement as men. However when swinging works it’s because the marriage was solid and happy to begin with. Swinging too is not a solution to a bad marriage.

So there are reasons to have extramarital sex and reasons not to have it, and large proportions of the adult population find themselves on either side of the divide. The question I want to deal with in this post is whether having extramarital sex is a smart or foolhardy thing to do.

Attitudes and morality

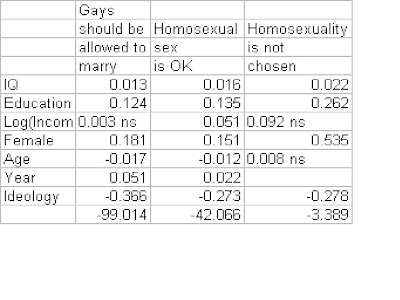

Let’s start with attitudes toward the acceptability of extramarital sex. Although the practice is very common, social norms in virtually every society are opposed to the open and flagrant practice of it. In the table entitled ‘Smart Vote Score’ the first 4 rows tell the tale of the acceptance of extramarital sex. Opinion differs strongly and systematically along IQ lines. Smart opinion fairly decisively rejects (and stupid opinion accepts) the notion that extramarital sex can never be OK. On the other hand this trend doesn’t imply that extramarital sex is generally OK either. The biggest ratio of smart to dull opinion was found on the “Extramarital Sex is Almost Always Wrong” option, and the next highest ratio on the “Sometimes Wrong” option. So while the bright are much more likely than the dull to think there are circumstances where extramarital sex is not immoral or a mistake, they are also more likely to think these circumstances are fairly unusual and rare. (Bright means an IQ over 116 and dull an IQ below 88.)

Moral philosophy agrees with the conclusion of the Smart Vote perfectly. It concludes that an affair is wrong most of the time but that there are exceptions. There are three basic approaches to morality – utilitarianism, deontology and virtue ethics. Justifications for affairs can be made in all three approaches. Utilitarianism says having an affair is wrong because it can hurt your spouse (as well as children, other family, friends and co-workers). On the other hand maybe you believe you and your affair partner stand to gain more than the sum of all the hurt, or that by not having an affair you (and your paramour) will suffer more than everyone else will gain in happiness. Maybe the person figures that even if it does create a net hurt in the short term in the long term things will be better for everyone. This approach is very demanding with respect to the foresight it requires, so even though it concludes exceptions are sometimes justified it also concludes that the odds are against a good outcome.

Deontology says affairs aren’t wrong because of consequences but because it involves violating important principles – like the duty to keep a promise, tell the truth or respect your spouse, or it violates the other’s right to fidelity, respect and the truth. However, most deontologists place conditions on duties and rights, e.g. ‘thou shalt not kill unless your own life is at risk’. A deontological condition for fidelity would be things like a spouse not neglecting their duty to see to your emotional needs. This approach requires less in the way of insight than utilitarianism because it refers to clear conditions around your rights and duties rather than guessing how a multitude of people will feel.

Virtue ethics says affairs should be avoided because they would smear those qualities that make you a good person – or character - even if only in your own eyes. Being honest, kind or wise are obvious examples of virtues one should strive to have to be a good person. Some that are outstanding with respect to certain virtues are deemed so good they are declared saints. Fidelity is generally seen as one of the virtues one should have to be a good person. Nonetheless sometimes virtues clash. For example one can be honest to the point of telling unkind truths that hurt, in which case you are failing to be kind, and perhaps failing to be wise too. Virtue ethicists such as Aristotle therefore argued that one not take any virtue to the extreme but try to find some balance or practice moderation. Goethe too preached balance. With respect to affairs there will be some circumstances where remaining faithful would not be virtuous e.g. where denying your own wellbeing is unwise and dishonest to yourself.

The justifications of moral philosophy aside, research suggests that one of the biggest contributing factors to affairs is simply opportunity. So those with greater means of controlling their time, and meeting people, are more likely to have affairs. In fact, the greater independence of men almost fully explains why they are more likely to have affairs. When the opportunity is the same, women have affairs as readily as men. That’s why it’s important to control for social class and income, along with marital happiness. The results of a multiple linear regression on attitude to extramarital sex (controlling for important confounding factors) can be seen in the table below entitled ‘Extramarital sex is not wrong’.

As expected, higher social class is associated with greater acceptance of extramarital sex (especially for men), and being older and more conservative with being less accepting of it. Unsurprisingly, marital unhappiness is clearly a major factor in accepting extramarital sex. There is also a trend toward less tolerance for affairs in more recent years. Nonetheless, even when all these risk factors are controlled, intelligence remains associated with accepting extramarital sex (at a very high level of significance for both sexes).

Behavior

Attitudes are one thing but actually engaging in extramarital sex is another. The 5th and 6th rows of the table above, entitled ‘Smart Vote Score’, show the ratio of smart to dull people who have actually had affairs, or haven’t had them, by gender. Bright men are 30% more likely to have affairs than dull men. Bright women are 50% more likely than dull women to have an affair. Alternatively bright men are 80% as likely as dull men to remain sexually faithful to their spouse. Bright women are only 75% as likely as dull women to remain faithful. (Bright means an IQ over 116 and dull an IQ below 88.)

The table entitled ‘Have had extramarital sex’ below shows the results of a logistic regression on having an affair with a number of risk factors controlled.

Unexpectedly, unlike with attitudes, social class doesn’t seem to play a role in actually having an affair. For men there is a similar trend toward less infidelity in recent years. Conservative men are also less likely to have affairs. There is a trend toward older men being more likely to have had an affair, no doubt because they had far more time. Again, as expected, marital unhappiness is associated with having affairs. Strangely age, ideology and the fashion of the day don’t have any significant effect on female infidelity. Still higher intelligence increases the odds of an affair even when all these risk factors are controlled. This result suggests that intelligent opinion leans toward the benefits of infidelity often outweighing the risks or costs.

Combining behavior and attitudes.

Interesting things happen when one combines attitude and behavior. I call those who both accept that extramarital sex is sometimes justified, and have had extramarital sex, ‘swingers’. Those who ethically accept that extramarital sex can be justified but haven’t been unfaithful I call ‘open’. Those who think extramarital sex is wrong but have had an affair anyway, I call ‘cheaters’. Finally those who consider infidelity to be wrong and have been faithful I call ‘traditional’. Rows 7-10 in the table above entitled ‘Smart Vote Scores’ show that brighter people support all options other than ‘traditional’ in greater proportions than do dull people. Nonetheless the ratio of smart to dull support for ‘cheating’ is close to equal. The Smart Vote is thus not for ‘cheating’ but goes to the ‘open’ group for men (although the ‘swinger’ group is pretty much the same) and strongly for the ‘swinger’ group for women.

The table entitled ‘Attitude and Behavioral Interactions on Extramarital Sex’ below shows the results of a multiple linear regression on the combination variable (scored as shown below the title) with the usual risk factors controlled.

For women being liberal and unhappily married move her from ‘traditional’ toward ‘swinger’. Other factors do not appear to matter much. For men, extra time to have an affair and the status of higher education also make the move more likely. The effect of higher intelligence still matters for men even after controlling for the risk factors (and comes close to significance for women). There is however some noise in this combination variable.

The graph below looks at the extreme groups – ‘swingers’ and ‘traditional’ (or rather ‘not traditional’). The chance of a person rejecting strict fidelity, in attitude, behavior or both – ‘not traditional’ - climbs from about 1/3rd for low IQs to around ½ for high IQs. The effect is slightly stronger for men. The chance of accepting both attitude and behavioral violations of marital sexual fidelity – ‘swinger’ - rises from 16% in low IQ men to just over 40% for very bright men. For women the change is even more marked – from 7% to 46%.

Many years ago I conducted some research relating a variety of personality scales to sexual attitudes and behavior in women. One of the personality scales was the California Psychological Inventory, which includes a scale called Intellectual Efficiency. This is a scale made up of personality items and interests that correlate highly with IQ. The total of this scale is so highly correlated to IQ that it can serve as a rough IQ test. I found that this scale correlated very highly with many sex related items – particularly those concerned with sexual permissiveness, and impersonal sex (or sex as recreation) such as swinging, sexual attraction toward women, group sex or orgies. Smarter women were very much more accepting of these activities. Alternatively, those who were accepting of these activities were much smarter than those who weren’t. They start expressing positive attitudes toward and admitting to taking part in some of these activities, when their IQs exceed around 130.

Summary

It appears that it’s silly to demand or expect strict sexual fidelity in marriage at all costs. It is often the sensible thing to do if trapped in an unhappy marriage, and not because it will help to preserve the marriage but because the marriage is probably not worth preserving. Also within happy and stable marriages swinging apparently adds spice to life without threatening, and usually enhancing, the relationship. The fact that the Smart Vote is for extramarital sex, implies that too much stress is being put on the costs, and too little on the benefits, of sexual relationships outside of marriage. Still, it is also silly to undertake sexual infidelity thoughtlessly. Most of the time, extramarital sex really is the wrong thing to do. Perhaps those who would struggle to think through the issues should avail themselves of help. My results suggest that anyone who isn’t smart enough to get through university should ask for wise independent council to help them think the issues through before embarking on extramarital sex.